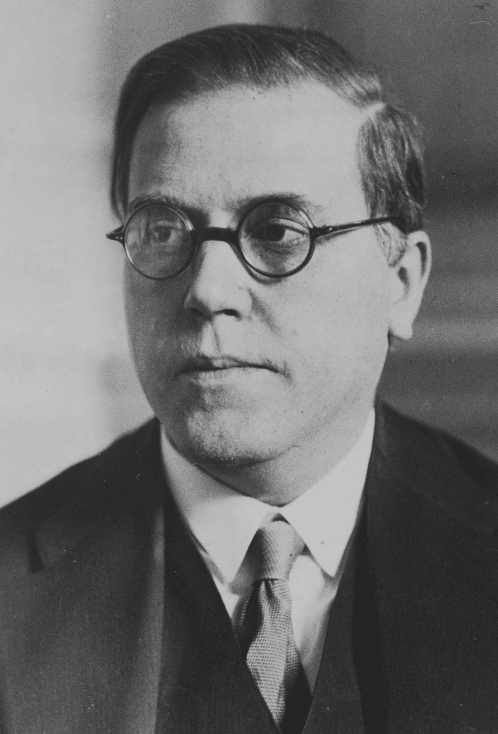

Dietrich von Hildebrand, the great Catholic philosopher and theologian, was one of the earliest and most vocal defenders of Pope St. Paul VI’s encyclical Humane Vitae. Hildebrand provides a coherent defense of natural family planning and condemnation of contraception in his book, The Encyclical Humanae Vitae: A Sign of Contradiction: An Essay on Birth Control and Catholic Conscience. Below is the relevant chapter from the book in which he distinguishes these practices:

15. Why artificial birth control is sinful but the rhythm method is not

The distinctions we have made above between the two concepts of nature shed new light upon the whole problem of artificial birth control. Above all, we are now in a position to see more clearly the decisive difference between rhythm and artificial birth control. We can now meet more decisively the objection: “Is it not also irreverent to have the explicit intention of avoiding the conception of a new human being without totally abstaining from the conjugal act?”

In the first place the value and meaning of the conjugal act is not affected by the married couple’s certainty that it cannot lead to conception. Having seen that this act in its very meaning is a unique expression of spousal love and a mutual donation of self, grounded in consensus, we now understand more clearly that this act is not only allowed, but is possessed of a high value even when conception is not possible. This meaning and value is explicitly recognized in the addresses of Pius XII, in the Council decree Gaudium et Spes, as well as in the encyclical Humanae Vitae.

In the second place it is definitely allowed expressly to avoid conception when the conjugal act takes place only in the God-given infertile time—that is, only by means of the rhythm method and for legitimate reasons. One would have to be blind to the meaning and value of the conjugal act to say that complete abstinence is morally required when conception is to be avoided for legitimate reasons.

It is clear, therefore, that in the intention itself of avoiding another child for serious reasons there is not the least trace of irreverence toward the mysterious fact that God has entrusted the birth of a person to the spousal love-union. We see that only during relatively brief intervals has God Himself linked the conjugal act to the creation of a man. Hence the bond, the active tearing apart of which is a sin, is realized only for a short time in the order of things ordained by God Himself. This also has a meaning. The fact that conception is restricted to a short time implies a word of God. It not only confirms that the bodily union of the spouses has a meaning and value in itself, apart from procreation, but it also leaves open the possibility of avoiding conception if this is desirable for serious reasons. The sin consists in this alone: the sundering by man of what God has joined together—the artificial, active severing of the mystery of bodily union from the creative act to which it is bound at the time. Only in this artificial intervention, where one acts against the mystery of superabundant finality, is there the sin of irreverence—that is to say, the sin of presumptuously exceeding the creatural rights of man.

Analogously, I may very well wish (and pray) that an incurably sick and extremely suffering man would die. I may abstain from artificially prolonging his life for a matter of hours or days. But I am not allowed to kill him! There is an abyss between desiring someone’s death and euthanasia. In both cases the intention is the same: out of sympathy I desire that he be delivered from suffering. But in the one case I do nothing that might prolong his suffering, whereas in the other I actively intervene and arrogate to myself a right over life and death that belongs to God alone.

Only when we see the divinely ordained limits to our active intervention, the limits that define what is allowed and that play a great role in the whole moral sphere, can we perceive the abyss separating the rhythm method from the use of all kinds of contraceptive devices.14

It is therefore desirable that science discover improved methods for ascertaining the infertile days. Pope Pius XII said that he prayed for this, and so should all Christians. Paul VI expresses this wish in Humanae Vitae, 24.

As soon as we see the abyss separating the use of rhythm from artificial birth control, we have answered the question: why should artificial birth control be a sin if the use of rhythm is allowed? And as soon as we see clearly the sinfulness of artificial birth control, we can and must repudiate the suggestion that it is the proper means of averting dangers that menace marital happiness or averting overpopulation. No evil in the world, however great, may be avoided through a sinful means. To commit a sin in order to avoid an evil would be to adhere to the ignominious principle: the end justifies the means.

14. This distinction between active intervention on our part and letting things take their course is also drawn in another situation: though no Catholic spouse is allowed to use contraceptive means, he is still not allowed to refuse the marital act even when his partner employs contraceptive means. Here also the distinction between the active and passive attitude is morally decisive.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.