Historical Testimony to an Infallible Primacy. Probably the earliest implicit attestation of papal infallibility came from Tertullian after his breach with Rome over the remission of adultery, declared to be valid, by Pope St. Callistus. “An edict has been published,” he protested. “The Pontifex Maximus, that is, the bishop of bishops, has made a decree: ‘I remit to such as have done penance the sins of adultery and fornication.” The ironical implication was that Callistus professed to be infallible in settling the issue under dispute, which Tertullian (already a heretic) simply denied.

Soon after, during the rebaptism controversy in Northern Africa, Pope St. Stephen was denounced by a recalcitrant bishop, Firmilian, for arrogating to himself the infallible power of deciding in favor of heretical baptisms: ‘Stephen, who brags so loudly of the seat of his episcopate and who insists that he holds his succession from Peter, on whom the foundation of the Church was laid.” Thus Firmilian testified to a papal claim of inerrancy in deciding on the conditions necessary for valid baptism, which, as subsequent history would show, fully vindicated the pope even when contradicted by forty bishops under the leadership of St. Cyprian.

In the mid-fourth century, Pope St. Julius rebuked the Eastern Arian bishops for condemning Athanasius on the score of heterodoxy. “Are you ignorant,” he asked, “that the custom has been for word to be sent to us first and then for a just decision to be proclaimed from this spot?” The historian, Sozomen (died 450 A.D.), adds that Julius told the bishops “it was an ecclesiastical law that whatever ordinances were made without the consent of the Bishop of Rome were counted void.” Anglicans and others who deny papal infallibility have accused Catholics of “deliberately mistranslating the text of the pope’s letter so as to apply to himself the words which really refer to all the Latin bishops, and show plainly that the pope made no such claim.” Against this charge stands all the manuscript evidence, plus the simple fact that ancient writers (like Sozomen) plainly understood Julius to mean that he personally, and not all the bishops of Italy, was the court of last appeal in settling doctrinal disputes.

Early in the fifth century, Pelagianism had spread from Britain to the eastern limits of the Mediterranean. According to this heresy, Adam’s sin was only the bad example he gave us and man’s will is so potent it may dispense with divine grace, except as a convenient aid, to attain the beatific vision. The bishops of Africa condemned Pelagius and referred their decision to the Bishop of Rome for approval. Pope Innocent I commended their action in a celebrated letter whose exact date, January 27, 417, has come down to us. “Following the examples of ancient tradition,” he told the prelates, “you have shown by your proper course of action the vitality of your religion, when you decided to defer to our judgment. You understand what is due to the Apostolic See, since all of us who are here (in the western world) desire to follow the Apostle from whom are derived this episcopate and all the authority belonging to this name. By following him we know how to condemn what is wrong and approve what is praiseworthy. Moreover in safe-guarding the ordinances of the Fathers with your priestly zeal, you certainly believe they must not be trodden under foot. They decreed, not with human but with divine wisdom that no decision–even though it concerned the most remote provinces–was to be considered final unless this See were to hear of it, so that all the authority of this See might ratify whatever just decision had been reached.” Innocent’s letter is fully extant, and through several columns of text reiterates the same profession of indefectibility in the face of Rome and duty of other churches to conform “to the norm and authority of the Church of Rome,” in doctrine as well as discipline.

The highpoint of historical testimony to papal infallibility was occasioned by a schism that Acacius, the patriarch of Constantinople, had started in the late fifth century. With Asia Minor split into hostile factions over the Monophysite heresy, the patriarch supported Emperor Zeno in promoting a doctrinal compromise, called the Henoticon, which Pope Felix III condemned. While critical of Nestorianism (one person in Christ), the Henoticon leaned towards Monophysitism (one composite nature in Christ) and therefore tacitly admitted that the Savior did not actually possess a true human nature. Acacius defied the pope, while an imperial decree imposed the Henoticon on all Christian subjects of the Empire. Communion with Rome was interrupted for nearly forty years, until the accession of Justinian, a Catholic and a Latin, to the throne of Constantinople.

Justinian ordered the Eastern bishops to sign a profession of faith which Pope Hormisdas had required of the Spanish hierarchy in 517. Known as the Formula of Pope St. Hormisdas, it unequivocally proclaims the unique preservation of error by the See of Rome, due to its solidarity with the Prince of the Apostles. “The first condition of salvation,” each bishop was to read, “is to keep the norm of the true faith and in no way to deviate from the established doctrines of the Fathers. For it is impossible that the words of Our Lord Jesus Christ who said, ‘Thou art Peter, and upon this rock I will build my Church,’ should not be verified. And their truth has been proved by the course of history, for in the Apostolic See the Catholic religion has always been kept unsullied.

From this hope and faith we do not wish to be separated under any circumstances…. Following the Apostolic See in all things and proclaiming all its decisions, we endorse and approve all the letters which Pope St. Leo wrote concerning the Christian religion (about the two natures in Christ). And so I hope I may deserve to be associated with you (the pope) in the one communion which the Apostolic See proclaims, in which the whole, true, and perfect security of the Christian religion resides.” Subsequent ecumenical councils accepted the profession as a doctrinal standard for the universal Church, and its solemn confirmation by later pontiffs raised the professio to the rank of a formal definition. Thirteen hundred years later the Vatican Council appealed to it as incontestable proof that the explicit declaration of papal infallibility in 1870 was only a clarification of the “perpetual practice of the Church,” as professed by the earliest ecumenical councils and especially those “in which the Eastern and Western Churches were united in faith and love.” When, five hundred years after Hormisdas, the Oriental Churches denied the primacy and separated from Rome, they went counter to the tradition of their Fathers who proclaimed the Apostolic See to be “the perfect security” of Christian revelation.[1]

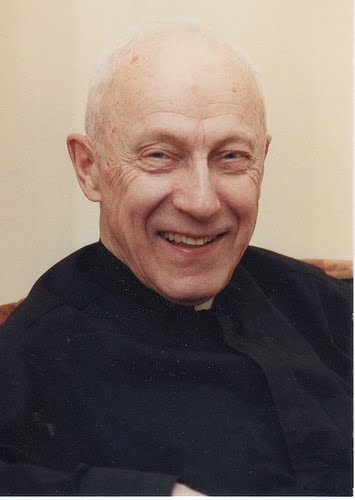

[1] https://hardonsj.org/christ-to-catholicism-papal-infallibility/

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.